Adverse Event reporting information can be found in footer

Request a Meeting

Nocturia, defined as waking up one or more times in the night to void urine,1 affects up to 60% of people over 70 years old and 17% of people 20-40 years old.2

Nightly awakenings to void are highly disruptive to an individual’s sleep and can lead to daytime sleepiness.3 Up to 83% of nocturia cases are caused by nocturnal polyuria (NP), a condition in which an abnormally large amount of urine is produced at night.4,5 Nocturia may be a key contributor to a reduced quality of life with a great impact on ability to function.3

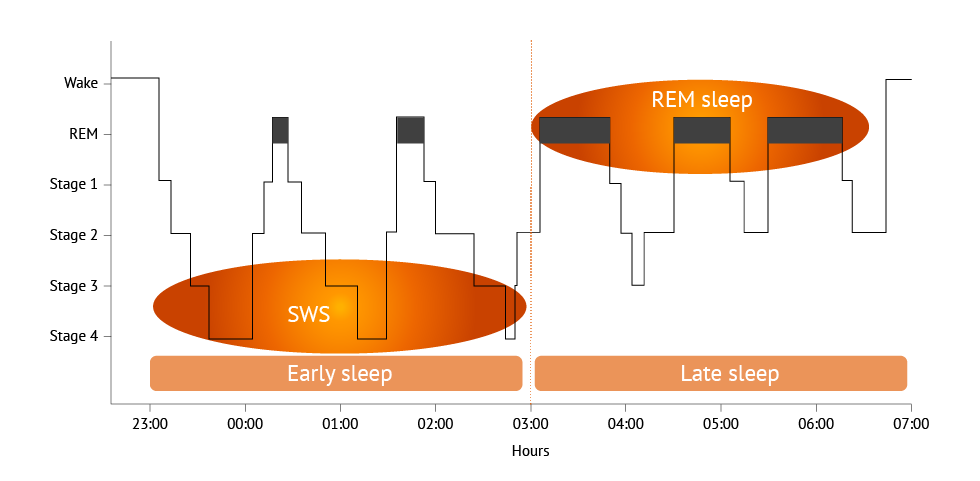

Sleep is characterised by cycles of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and non-REM sleep.6 Non-REM sleep includes light sleep stages 1 and 2, and slow-wave sleep (SWS) stages 3 and 4 (deep sleep).6 SWS, which occurs during the early hours of sleeping,6 is responsible for the majority of the restorative night’s deep sleep.7 SWS supports initial memory encoding thereby allowing the brain to prepare for learning, facilitates the processing of memories and allows consolidation of new memories.8

Adapted with permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: Nat Rev Neurosci, Diekelmann S & Born J. The memory function of sleep. 11:114-126. Copyright 2010.

Poor sleep is associated with deficits in daily functioning such as:

Reduced mental functioning can lead to lower capabilities and efficiency of task performance, increased number of errors and an impaired ability to learn.12,13 This is caused by impaired perception, difficulties in keeping concentration, vision disturbances, slower reactions and temporary episodes of sleep or drowsiness.13

Low sleep quality is associated with reduced health and quality of life:3,11-16

Interruption of SWS in particular is associated with reduced insulin sensitivity, impaired glucose tolerance, obesity and an increased risk of type 2 diabetes.7,17

Older adults more commonly suffer with nocturia and sleep problems than younger adults; ageing is particularly associated with a reduction in the amount of SWS.2,10 Since increasing age is associated with concomitant conditions that affect sleep, such as depression, physicians should ask their older patients whether they have problems with sleep and any issues that arise from this.10

Poor sleep quality brings problems not only for individuals, but family and society also.3 Patients with NP are likely to need to wake up to urinate during the night.3 As NP is one of the causes of nocturia, it should be a target of intervention to reduce nocturia and the burden of sleep fragmentation.3-5

Job Code: UK-NOQD-2000015 - Date of preparation: January 2023